And some there be, which have no memorial;

who are perished, as though they had never been; and are become as though they

had never been born; and their children after them. Sir 44:9

African

Americans founded Decoration Day (the former name of Memorial Day) at the graveyard of 257 Union soldiers labeled

"Martyrs of the Race Course," May 1, 1865, Charleston, South

Carolina.

The

"First Decoration Day," as this event came to be recognized in some

circles in the North, involved an estimated ten thousand people, most of them

black former slaves. During April, twenty-eight black men from one of the local

churches built a suitable enclosure for the burial ground at the Race Course.

In some ten days, they constructed a fence ten feet high, enclosing the burial

ground, and landscaped the graves into neat rows. The wooden fence was

whitewashed and an archway was built over the gate to the enclosure. On the

arch, painted in black letters, the workmen inscribed "Martyrs of the Race

Course."

At nine

o'clock in the morning on May 1, the procession to this special cemetery began

as three thousand black schoolchildren (newly enrolled in freedmen's schools)

marched around the Race Course, each with an armload of roses and singing

"John Brown's Body." The children were followed by three hundred

black women representing the Patriotic Association, a group organized to distribute

clothing and other goods among the freedpeople. The women carried baskets of

flowers, wreaths, and crosses to the burial ground. The Mutual Aid Society, a

benevolent association of black men, next marched in cadence around the track

and into the cemetery, followed by large crowds of white and black citizens.

All dropped

their spring blossoms on the graves in a scene recorded by a newspaper

correspondent: "when all had left, the holy mounds — the tops, the sides,

and the spaces between them — were one mass of flowers, not a speck of earth

could be seen; and as the breeze wafted the sweet perfumes from them, outside

and beyond ... there were few eyes among those who knew the meaning of the ceremony that was not dim with tears of joy." While the adults marched

around the graves, the children were gathered in a nearby grove, where they

sang "America," "We'll Rally Around the Flag," and

"The Star-Spangled Banner."

The official

dedication ceremony was conducted by the ministers of all the black churches in

Charleston. With prayer, the reading of biblical passages, and the singing of

spirituals, black Charlestonians gave birth to an American tradition. In so

doing, they declared the meaning of the war in the most public way possible —

by their labor, their words, their songs, and their solemn parade of roses,

lilacs, and marching feet on the old planters' Race Course.

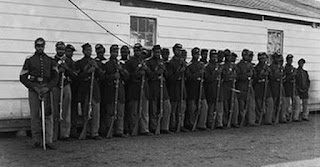

After the

dedication, the crowds gathered at the Race Course grandstand to hear some

thirty speeches by Union officers, local black ministers, and abolitionist

missionaries. Picnics ensued around the grounds, and in the afternoon, a full

brigade of Union infantry, including Colored Troops, marched in double column

around the martyrs' graves and held a drill on the infield of the Race Course.

The war was over, and Memorial Day had been founded by African Americans in a

ritual of remembrance and consecration. (Race and Reunion: The Civil War in

American Memory, Professor David W. Blight )